Back Then, When We Got Along

There was a time when the Colorado plains were not empty, but a bustling crossroads of nations and commerce, a world unto itself.

In the 18th century, explorers, adventurers, hunters and trackers trekked across the Great Plains, climbed the steep passes of the the Rocky Mountains, ventured to the Great Northwest. Countless numbers remained on the plains, hunting, trapping, and marrying into the various indigenous tribes, and with the aid of their new native families, thrived.

If this world had a capital, it would have been a fragile castle of mud and straw, built on a dream of profit and a need for peace. It was known then as Bent’s Fort—a place that existed for a mere sixteen years but left a shadow so long it still stretches across the Arkansas River today. It was a place where danger was a constant companion, but where trade, culture, and power came together in a way that would never be replicated.

When Bent's Old Fort was built, the territory was part of the sovereign nation of Mexico, yet strategically located on the U.S. north side of the Arkansas River—the internationally recognized border between the United States and Mexico. It was built in 1833, more than a decade after Mexico had gained its independence from Spain. The Mexican War of Independence had ended just a dozen years before with the signing of the Treaty of Córdoba.

At the time of the fort's construction, Mexico was a young and politically unstable nation. The fort's location allowed the trading post to capitalize on the lucrative trade along the Santa Fe Trail. The fort's success was deeply tied to its relationships with the Mexican government, a connection that would have been impossible during the strict colonial rule of the Spanish Empire.

For much of its 16-year history, the Bent, St. Vrain & Company maintained strong economic and legal ties to what is now the U.S. state of New Mexico. They maintained stores in Taos and Santa Fe, on the Mexican side of the border. This cross-border commerce was central to their success. The fort’s status as a gateway between two nations came to an abrupt end with the Mexican-American War in 1846, which resulted in the U.S. acquiring a vast amount of Mexican territory, including what is now Colorado and New Mexico.

The venture was ambitious and the men behind it weren’t born on the frontier. They hailed from the same city that served as the gateway to the West, St. Louis, but they were products of a burgeoning American West.

The Bent brothers, Charles and William, were sons of a prominent judge. Ceran St. Vrain came from a French aristocratic family that had also settled there. All three were well-educated, and all were drawn to the excitement and promise of the fur trade. Ceran St. Vrain, in particular, was an experienced trader who had spent years in New Mexico, even becoming a naturalized Mexican citizen to get ahead of the trade restrictions on American merchants.

By the late 1820s, Charles and St. Vrain had formed a partnership, realizing that the old model of trapping was giving way to the more profitable business of trading manufactured goods for furs and buffalo robes. William, the youngest of the trio, joined them around 1831, bringing his own skills and knowledge of the plains tribes.

Their partnership, called the Bent, St. Vrain & Company, was a masterclass in business strategy. They were entrepreneurs who understood a diverse market. As the website Legends of America notes, they "insulated themselves against an economic downturn in any one of these respective ventures" by participating in the fur, tribal, and Santa Fe trade.

Charles Bent, the oldest and most business-savvy, took up residence in Taos, New Mexico, where he managed the company's stores and political dealings. Ceran St. Vrain, known as a successful trader and businessman, also operated out of Taos and Santa Fe, but was a key figure in their ventures across the entire region. William, the youngest, became the heart and soul of the fort, living and working there, cultivating the deep relationships with Native American tribes that would become the foundation of their success. It was a division of labor that worked beautifully, and for a while, they were the second-largest fur company in the American West, second only to John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company.

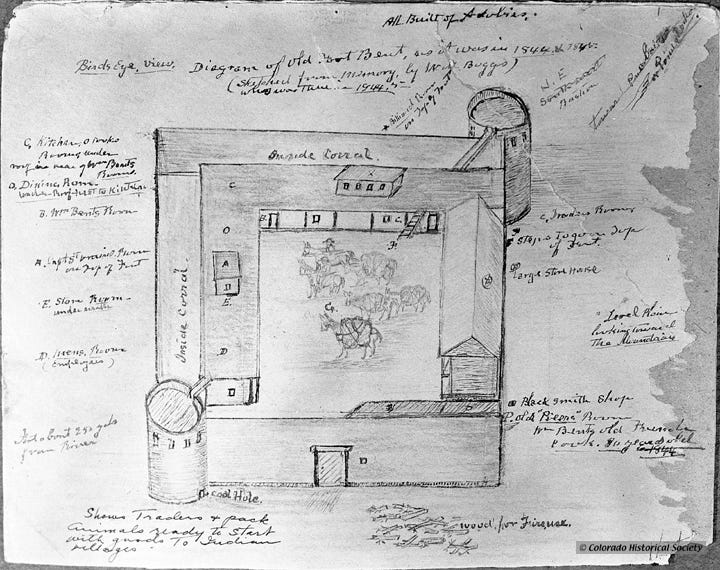

The fort itself was a monumental undertaking, built of adobe bricks, a material common in Mexico but new to the American fur trade. As the National Park Service notes, on their website NPS History, the traders "turned to adobe, a building material long favored by Mexicans," mixing clay, water, and sand with straw or wool to create a sturdy, lasting structure.

The name "Bent's Fort" was a bit of a misnomer; its official name was Fort William, after William Bent, who oversaw its construction and daily life. But the Bent, St. Vrain & Company name was what gave it power.

The fort’s real power was in its carefully built relationships with the Native American tribes of the Southern Plains. This was not a place of conflict, but a place of diplomacy. The primary trading partners were the Southern Cheyenne and the Arapaho, who had been pushed into the area by the Sioux and other tribes. The Bents, particularly William, made a conscious effort to understand and work within the tribes’ cultural norms.

As a UC Press E-Books Collection states, the alliance between the traders and the tribes "fits within the pattern of traditional behaviors," where gift-giving and a reciprocal relationship were more important than a simple commercial transaction. The traders understood that their identity and prestige were intertwined with these relationships, not just their profit margin.

The personal connections were the most crucial. William Bent forged a particularly deep bond with the Cheyenne. He married Owl Woman, the daughter of a prominent chief named White Thunder, in a union that was as much a political alliance as it was a personal one. The marriage was a symbol of trust and partnership, and it provided Bent with an invaluable link to the Cheyenne council.

Owl Woman’s sister, Yellow Woman, would become his second wife after Owl Woman’s death, further cementing this alliance. Their children, including sons Robert and George, grew up bicultural, moving between the Cheyenne world and the fort’s “cosmopolitan” life. The fort became a neutral ground where the Cheyenne and Arapaho could live in relative peace and security.

As the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum notes, entire villages would camp within the fort’s walls, and even rival tribes could come together for peaceful trade. This was a testament to the respect and trust that William Bent had earned.

The lifeblood of the fort wasn’t just beaver pelts, though those were important in the early days. As the market for beaver declined, the real power was in the buffalo robe trade. It was a business that transformed the Southern Plains, turning a source of life into a unit of currency. As an expert on the fur trade, Bill Gwaltney of the National Park Service, is quoted in Colorado Life Magazine saying, the trade "changed the buffalo from being something they lived off of into currency, the way they buy other things." This shift had immense consequences, fueling a demand that led to the overhunting of the herds and, eventually, a crisis. But for a time, it was a wildly profitable enterprise.

The fort's traders would exchange about 25 cents worth of goods—things like gunpowder, beads, and food—for a buffalo hide. Those same hides, bundled and shipped east on the Santa Fe Trail, could fetch up to $6 each in St. Louis. The fort shipped out as many as 15,000 robes a year, a mind-boggling number that tells you everything you need to know about value of its location.

Within the fort's adobe walls, the world of the 1840s West unfolded. It was a bustling, chaotic place, a "babel of a place," as one journal described it, where seven or eight languages might be heard at any given time. Spanish was the most common, a testament to the fort's ties with New Mexico. Cheyenne, Arapaho, English, and French also mixed in the trade rooms and courtyards.

William Bent was particularly close to White Thunder, one of the Cheyenne leaders, and the Cheyenne themselves advised the Bents to build their permanent trading post where the fort now stands. The fort was a hub of exchange, not just of goods, but of ideas, customs, and even family.

The fort’s power was also a military one, though not in the traditional sense. It became a neutral ground in a landscape of constant tension. Ceran St. Vrain, a key partner, made it clear that the fort was established, according to NPS.gov "for the purpose of trading with the several tribes of Indians in its vicinity." Their diplomacy was often more effective than any army. Yet, the fort’s neutrality was tested and ultimately broken by the machinations of a different kind of war.

In 1846, with the U.S. declaring war on Mexico, the fort became a staging ground for Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny's "Army of the West." The military's presence, while a boost to the fort's business in some ways, also disrupted the delicate balance of the trade system. It was the beginning of the end.

The fate of the three partners diverged dramatically in these final years. Charles Bent, ever the man of ambition, was appointed the first American civil governor of New Mexico by Kearny. It was a high honor, but it would be his undoing. In January 1847, he traveled to his home in Taos without military escort, believing the region was secure. He was wrong. The Taos Revolt, an uprising of Mexican and Pueblo Indian insurgents against American rule, erupted, and Bent was murdered in his home, according to the Britannica.

The rebels "scalped him alive," a brutal act that cemented his legacy as a victim of the chaotic frontier. Ceran St. Vrain, who was also in Taos at the time, quickly organized a force of volunteers to join the American troops and suppress the rebellion. He was a key figure in ending the revolt, an act that secured his reputation and his future in New Mexico.

The final years of the original fort were a perfect storm of disaster. The war with Mexico ended in 1848, but the fort’s old way of life was already gone. The overhunting of bison had diminished the herds, and a cholera epidemic, brought in by travelers on the trail, swept through the region in 1849. It decimated the Native American population, the very people who were the fort's primary trading partners.

The commercial enterprise was no longer profitable. William Bent tried to sell the fort to the U.S. Army, but a low-ball offer of $12,000 was a final insult. According to an account from Bent’s son, George, recounted on the University of Northern Colorado website, "after the Mexican War the fur business had fallen off to such an extent that it was no longer profitable to maintain large trading posts, so when the War Department offered to buy Bent's Fort and turn it into a military post, my father said that he was willing to sell. The government, however, offered him only $12,000, and . . . he refused to sell, abandoned the fort and blew it into the air."

While it wasn't completely destroyed, Bent's symbolic act of defiance marked its end. The original structure would be used as a stagecoach station for a time, but by the 1880s, local settlers had hauled away most of the remaining adobe bricks for their own homes. By 1900, the "castle on the plains" was a mere pile of rubble.

After the fort’s demise, the lives of the surviving partners continued. Ceran St. Vrain retired from the trading business and became a successful businessman in New Mexico. He diversified his interests, establishing a flour mill that supplied U.S. Army forts and publishing the Santa Fe Gazette. He was a respected figure, a "gentleman of the old school," as he was often called, and he died in Mora, New Mexico, in 1870.

William Bent, in the meantime, continued his life on the plains. He established a new post, Bent's New Fort, further downstream, and for a time he was a U.S. government agent for the Upper Arkansas tribes, trying to mediate peace in an increasingly hostile environment. But his efforts were largely unsuccessful. The government’s policies were pushing the tribes onto smaller and smaller reservations, and the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864, an atrocity against the Cheyenne that killed many of his own family members, was a crushing blow. Bent spent the last years of his life in seclusion on a ranch and died in 1869, a year before his old partner. The new fort fell into disuse. The era they helped create was well and truly over.

For decades, the fort was nothing but a memory and a pile of ruins located just off Colorado Hwy. 194, roughly halfway between Las Animas and La Junta. Its significance was not forgotten, however, and in 1960, the site became a National Historic Site. It was decided that this important piece of history should be rebuilt. As the National Park Service explains, archaeological excavations and original sketches from people like Lieutenant James W. Abert were used to guide the reconstruction, which was undertaken in the 1970s as a bicentennial project. On July 25, 1976, the new fort was dedicated. It was meant to be a physical, tangible link to the past, a way for people to "step back in time."

For years, that’s exactly what it was. The fort became a renowned "living history" site, where reenactors and park rangers brought the past to life. They portrayed everyone from blacksmiths and traders to soldiers and trappers. It was a powerful illusion, a way for visitors to smell the woodsmoke, hear the blacksmith’s hammer, and imagine what it was like to be at the center of the 19th-century West.

Retired reenactor and living history practitioner, Mike Carson, is quoted in The Colorado Sun saying, "From the very first day, Bent's Fort has been known as a dang good living history site, where folks could visit and get an idea of what life would've been like here in the middle of nowhere in the 1830s and '40s. The place would come alive." But this seemingly perfect recreation is now facing its own set of challenges, a new kind of danger, as recent reporting from CPR News reveals. https://coloradosun.com/2024/02/27/bents-old-fort-national-historic-site-changes-southeastern-colorado/

Recent reporting from CPR News reveals that the reconstructed fort is grappling with both structural issues and a philosophical debate about how to best tell its story. In recent years, the adobe structure has shown its age. The second story of the fort was closed due to failing timbers, and a major snowstorm exacerbated the problems, leading to the temporary closure of the entire main building.

Superintendent Eric Leonard, in a statement to CPR News, affirmed the National Park Service’s commitment, stating, "We are committed to preserving this important site and its story. This temporary closure will allow the National Park Service to assess the extent of the damage and begin work to stabilize the structure, once again providing a safe environment for visitors and employees." These are not small problems, and they have led to a controversial proposal from the park service to have the reconstructed building designated as a "non-historic structure."

This proposal has raised alarms among preservationists. Dawn DiPrince, the State Historic Preservation Officer for Colorado, pushed back on the idea in a conversation with CPR News. While acknowledging the fort’s poor condition, she stated, "We know how dire things can look, but we also know how fixable they are." She believes that the deteriorating adobe is "a very redeemable, fixable situation." DiPrince's concern is that without proper care, the fort could face a slow demise.

She told CPR News that while she's not worried about demolition, "demolition by neglect is always something that I worry about, not just at this site." The park service, for its part, is now offering limited ranger-guided tours to allow visitors back into the building, a move that Leonard, in a press release cited by CPR News, said they were "excited to invite the public back into the reconstructed fort through guided tours."

And based on recent reporting, Bent's Old Fort is facing significant challenges due to budget and staffing cuts under the current administration. The issues with the fort's adobe structure and the debate over its "living history" programs are now taking place within a broad political context of nationwide cutbacks. Our nation’s history seems to not be important to this administration.

The recently passed spending bill includes a cut of more than $1.2 billion for the National Park Service, which would be the largest reduction in the agency's 109-year history. This proposed cut of over 36% to the NPS budget is part of a larger plan to reduce funding for public land agencies by more than a third of their 2024 levels. As a result, the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA) estimates that the funding for up to 350 national park sites could be effectively ended or transferred to states.

These budget proposals are already having an impact on staffing. Since January, the National Park Service has lost about a quarter of its permanent staff, a drop of more than 4,000 employees. Reports from various sources indicate that the administration's staffing cuts are leading to reduced visitor services, delayed maintenance, and canceled educational programs across the country. These cuts are not just affecting Bent’s Old Fort, but also parks like Yosemite scores of other historic locations and monuments.

At Bent's Old Fort, the ongoing structural issues with the adobe walls require significant and specialized maintenance. The recent temporary closures and the park's proposal to reclassify the reconstructed fort as a "non-historic structure" are part of a complex discussion about its future. Without funding, the fort faces a grim future.

The NPS has already had to make tough decisions, such as a shift away from certain living history programs and a reduction in livestock, due to a lack of dedicated staff and resources. This nationwide pressure on funding and staffing could further complicate the ability of sites like Bent's Old Fort to address their long-standing maintenance and preservation needs.

Beyond the physical state of the building, the very nature of "living history" at the fort is under scrutiny. Superintendent Leonard has been upfront about the need for change, telling CPR News that living history programs could see changes in how livestock are managed and how the fort’s diverse history is represented. He questioned the past practice of having white Americans portray African-American or Mexican laborers, calling it disrespectful and not inclusive.

Leonard emphasized, "as a national park, Bent's Old Fort has an obligation to tell the story of this place to all Americans" (CPR News). He believes the large, costly events of the past are not sustainable and that a shift to "smaller things more often" would be better. He's also been clear that the concept of living history won't disappear, telling CPR News, "There should always be more than one tool in the toolbox, and living history will always be a part of what Bent's Old Fort does." It's a recognition that the story of this place is more than just one perspective. Leonard is now facing criticism from the administration over those remarks.

The history of Bent's Old Fort has not been a simple, linear narrative. It is a story of ambition, diplomacy, and the clash of cultures on a dangerous frontier. It is a story of a place that was built, destroyed, and then rebuilt, only to face new threats from within and without. The original fort was a temporary miracle of peace and profit in a time of great change, and its legacy is a place where we still grapple with how to honor and represent that complex history.

In both its original form and its modern reconstruction, Bent's Old Fort remains what it was always meant to be: a crossroads of history, culture, and, even a little bit of danger.

We have an event next Saturday at the Manzanar War Relocation Center. I hope every park and monument gets some love.

https://sierrawave.net/manzanar-committee-co-sponsors-npca-national-day-of-action/