Following the Korean and Vietnamese conflicts, we used to say that wars were how Americans learned geography. Well, Trump’s fanciful policies are how Americans are learning the mistakes our nation has made over its two and a half century life.

If nothing else, Donald Trump provides an opportunity to educate.

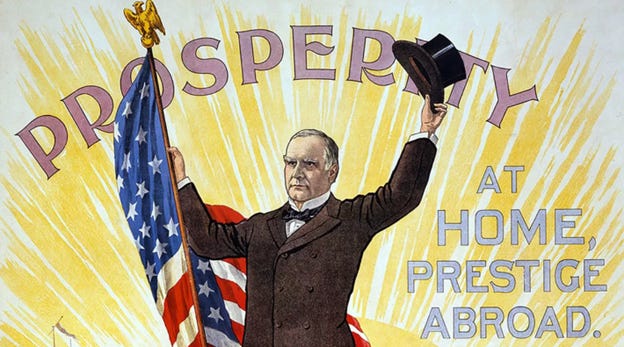

Donald Trump changes his mind as often as he changes his diaper. On his first day back in office, Trump praised his new presidential role model, William McKinley. Matt Welch, editor at large at Reason Magazine, noted that our feckless leader said McKinley had “made our country very rich through tariffs.” Trump then signed an executive order to change the name of the highest mountain in North America back to “Mount McKinley,” instead of Denali.

That went over like a lead Yeti.

According to Trump’s executive order, McKinley, the 25th president, "heroically led our Nation to victory in the Spanish-American War. Under his leadership, the United States enjoyed rapid economic growth and prosperity, including an expansion of territorial gains for the Nation. [He] championed tariffs to protect U.S. manufacturing, boost domestic production, and drive U.S. industrialization and global reach to new heights."

Well, the Orange Man hasn’t a clue of what he’s talking about. To paraphrase Senator Lloyd Bentsen in the 1988 Vice Presidential Debate—when he told Dan Quayle he was no John F. Kennedy—I (metaphorically) knew William McKinley. You’re no William McKinley.

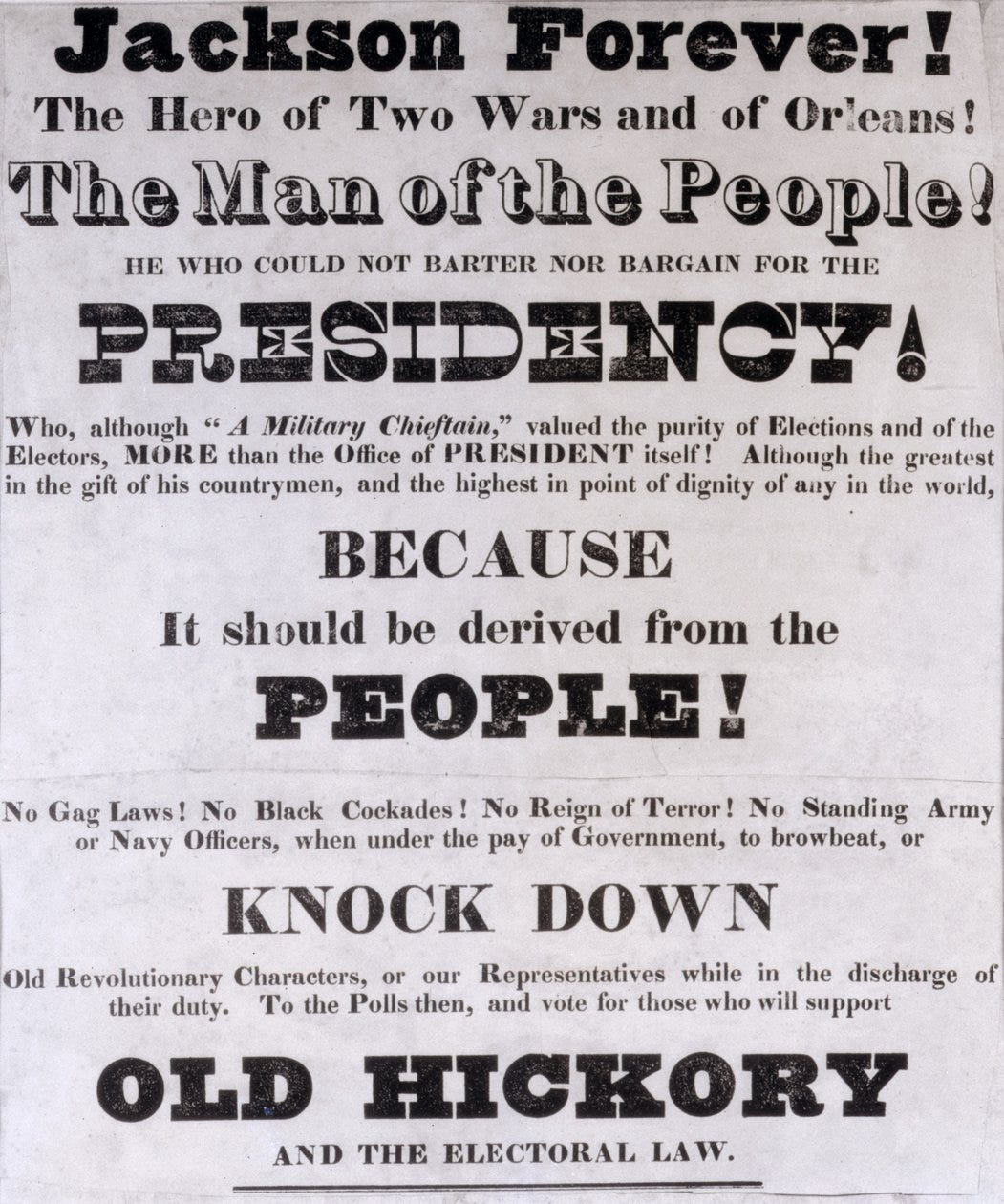

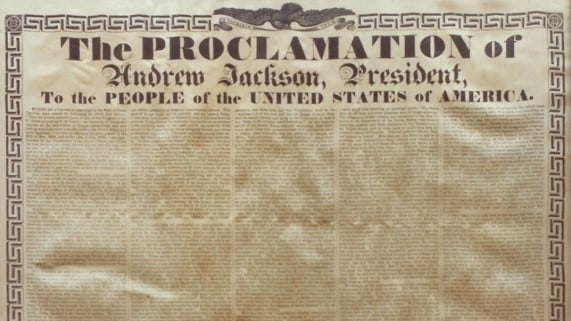

Trump’s fascination with the 25th president is both unusual and telling. In his first term, the object of his fascination was “Old Hickory,” Andrew Jackson, the 7th president—known for his inhumane treatment of Native Americans and the Trail of Tears. Yet Jackson is also remembered for his strong belief that the young nation would survive and grow. That image somewhat matched Trump’s self-image as a tough guy.

But McKinley?

Trump may admire both presidents, but they contradict in many ways. One thing they had in common, though, was their connection to tariffs. Former Congressperson Christopher Cox pointed out that Andrew Jackson won the presidency in 1828 partly because he opposed the very high tariffs passed by Congress that year. Southern critics called it the “Tariff of Abominations.”

Inversely, Douglas Irwin, a professor of economics at Dartmouth and a leading expert on McKinley, describes the 25th president’s policies: “This whole late 19th century was a period of expansion,” he said. “Tariffs themselves probably didn’t make a huge amount of difference one way or another.”

McKinley and Jackson, presidents from different centuries, both played major roles in America’s history with tariffs. But their goals and circumstances were not the same. William McKinley was one of the strongest supporters of tariffs in American history. He believed these high tariffs were needed to protect American factories and workers from foreign competition, especially as the country was becoming more industrial.

On the other hand, Andrew Jackson had a more practical and political view of tariffs. He got tangled up in one of the biggest tariff disputes in U.S. history—the Nullification Crisis of 1832. High tariffs from 1828 and earlier had caused outrage in the South, especially in South Carolina. Southern states, which relied on farming and imported goods, believed that high tariffs were hurting them. When South Carolina claimed it could ignore federal tariff laws, Jackson—though usually a supporter of states’ rights—stood firm on national unity. He passed the Force Bill, saying he would use the military if needed to enforce federal law. He made it clear: no state had the right to break away or ignore the union.

So, while McKinley used tariffs to grow industry and build up the nation’s economy, Jackson dealt with tariffs as a threat to the unity of the United States. McKinley supported tariffs as a way to shape America’s future. Jackson dealt with them as a crisis that could break the country apart. For McKinley, tariffs were about independence from other countries. For Jackson, it was about whether states could go against the federal government.

There’s also a difference in the people they represented. McKinley’s support came mostly from the industrial North, the “Robber Barons,’ where tariffs helped growing factories. Jackson had support from the South and West, the “little people” in farming areas where tariffs made life harder. But Jackson was willing to challenge powerful Southern leaders to keep the country together. Meanwhile, McKinley used tariffs to unite different regions under one economic plan.

Tariffs have long been a hot topic in America. They have played a major role in the Civil War and the Great Depression. Now, they may once again become a major dividing line. Based on the huge number of people protesting in cities around the country—and the world—it looks like that possibility is real.

Trump’s “America First trade policy” included new tariffs, which he said would protect American jobs and factories from foreign competition: a return to what he called “economic nationalism.” He even said that the word “tariff” was “the most beautiful word in the dictionary.”

It seems that Trump had turned away from his first role model, Andrew Jackson.

Trump’s strong belief in protectionism is a big shift from the free-trade views that most presidents—especially Republicans—have followed since World War II. His language and policies have caused tension inside the conservative movement. Still, most Republican leaders haven’t stood up to him. Those who support Trump often say that his “tariff talk” is just tough talk used in negotiations. Others worry that he is pushing the Republican Party away from its free-market beliefs.

Following Trump’s recent, massive wave of global tariffs (remarkably sparing Russia but somehow ensnaring penguins, seals, and polar bears) it’s hard not to draw historical parallels, although I doubt that he knew much about the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, until after he had his mind set on making the same error.

And this is where I don my historian’s cap: To understand Smoot-Hawley, we must go back to the years before it was passed.

After World War I, the government had provided heavy price supports to boost farm production. The goal was to help feed war-torn Europe and supply food during the conflict. American agriculture ramped up, running at full speed, but by 1920, Europe’s farms had recovered, and the demand for U.S. exports fell. At the same time, the U.S. ended those wartime supports. Farmers were left producing too much, with too little demand. Corn prices, for example, dropped to as low as 40 cents per bushel in the early 1920s and rarely rose above 90 cents for the rest of the decade. This period—1920 to 1928—was a deep agricultural depression, even though the broader economy was booming during the “Roaring Twenties.”

Farmers began calling on the government for help. Many believed that tariffs could raise prices by limiting competition from cheaper foreign products. This movement gained traction just as Herbert Hoover, a proud son of Iowa and known for his humanitarian work during and after WWI, campaigned for the presidency in 1928. He promised to support America’s farmers and promote economic growth.

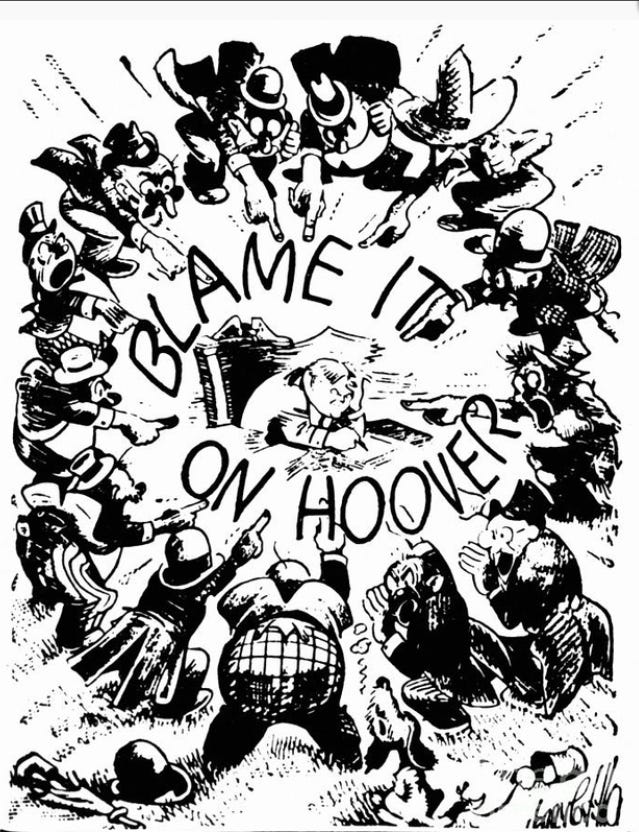

Hoover was elected president. But within a year, in October 1929, the stock market crashed and the U.S. economy began spiraling into what would become the Great Depression. In response to rising fears and falling prices, the idea of using tariffs to shield American producers grew even more popular.

That’s when Senator Reed Smoot of Utah and Representative Willis C. Hawley of Oregon stepped in. Both Republicans, they sponsored a bill to sharply raise tariffs on a wide variety of goods—not just farm products but also manufactured items, textiles, and consumer goods. Their goal was to protect U.S. jobs and industries from foreign competition during hard times.

The bill made its way through Congress, gathering support from lawmakers hoping to protect their local industries. But even as it moved forward, alarm bells were ringing. Over 1,000 economists from around the country signed a public petition urging President Hoover not to sign the bill. They warned that these high tariffs could provoke a global trade war. Prominent newspapers, business leaders, and even some of Hoover’s advisors joined the opposition. Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company and a loyal Republican, personally visited the White House to argue against the bill. International leaders warned that if the U.S. raised its trade barriers, they would retaliate.

But Hoover, caught between his economic advisers and a Republican Congress demanding action, made his choice. In June 1930, he signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act into law. It raised tariffs to an average of 40% to 60% on more than 20,000 imported items, making it one of the highest tariff levels in U.S. history.

The consequences were immediate and devastating.

America’s trading partners quickly responded with retaliatory tariffs of their own. Canada, then the U.S.'s biggest export market, imposed stiff duties on American goods. Countries across Europe followed suit. Instead of protecting American industries and farmers, the act triggered a global trade war. Exports fell sharply. U.S. farmers, who had hoped the tariffs would help them, now faced even lower prices as international markets closed off.

The numbers were staggering: world trade dropped by about 65% between 1929 and 1933. American exports were cut in half. Many businesses collapsed. Farmers lost their land and were left to seek jobs in cities where jobs were scarce. Unemployment soared. Instead of boosting the economy, the tariffs helped deepen and prolong the Great Depression.

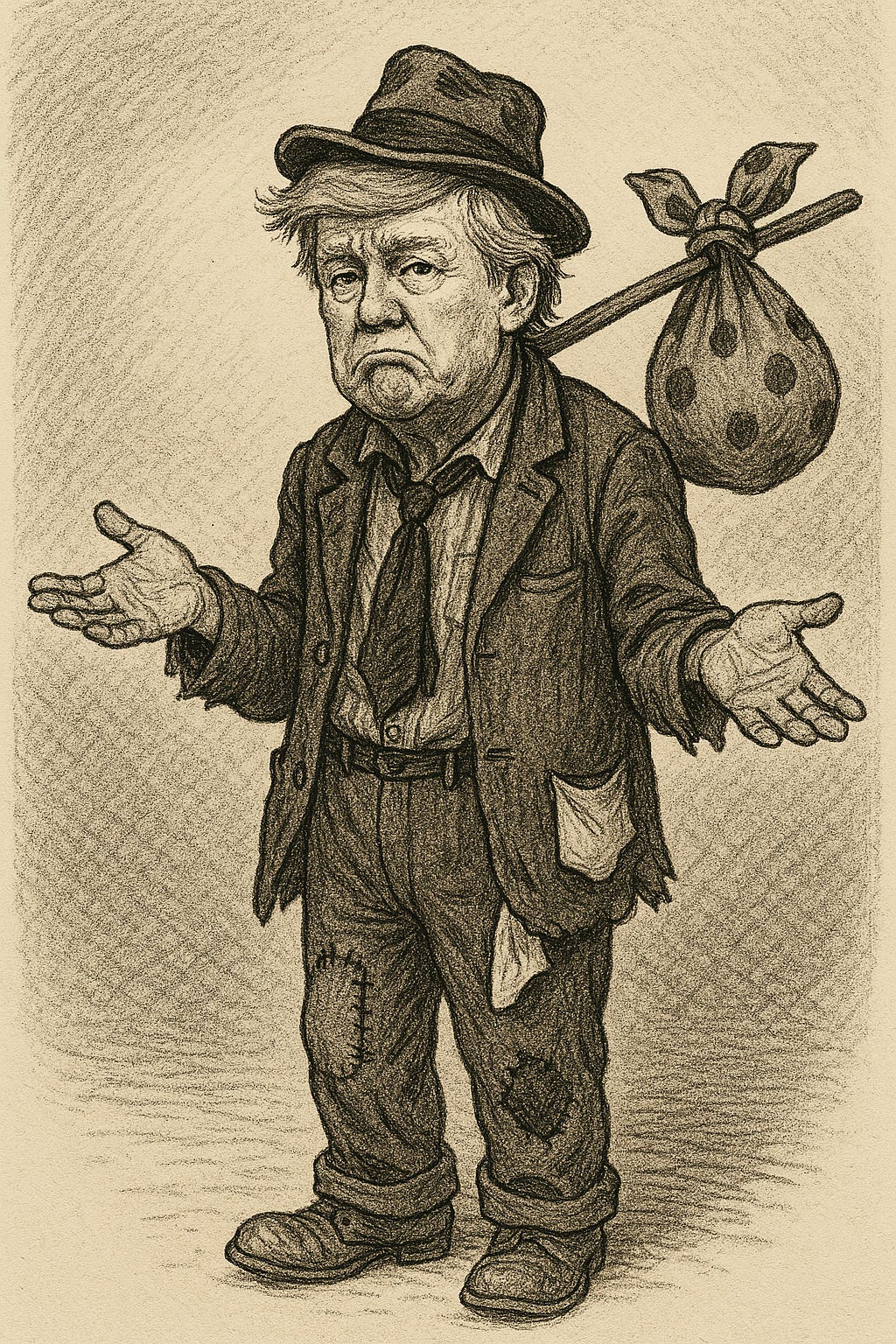

Hoover’s reputation suffered greatly. Though he had tried to respond to the economic crisis, his support for Smoot-Hawley made him seem out of touch. In the 1932 election, Franklin D. Roosevelt won by a landslide, in part by promising to undo the damage caused by the tariff war. In 1934, Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, which reduced tariffs and marked a shift toward trade liberalization and cooperation with other nations.

Over time, economists and historians came to see Smoot-Hawley as a major policy failure. It is often cited in textbooks as a classic example of how protectionism can backfire—hurting the very people it is meant to help and triggering broader economic fallout. The long shadow of Smoot-Hawley helped shape U.S. trade policy for decades. After World War II, American leaders helped establish the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and later the World Trade Organization (WTO) to prevent similar trade disasters and promote global economic stability.

We should know better, and if our education systems weren’t broken we probably would know better, but here we are, hearing the echoes of Smoot-Hawley reappear—loud and clear.

Trump’s return to high tariffs, under the banner of “America First,” sounds familiar to those who know their history. While Trump may claim kinship with McKinley, his broad and scattershot tariff policies resemble Smoot-Hawley in their chaotic implementation, nationalist rhetoric, and potential for worldwide economic disruption. Just like in 1930, many economists today warn that sweeping tariffs—especially without international cooperation—can hurt more than they help.

Trump's current tariff push is driven by a deeply rooted misunderstanding of economics, particularly his belief that trade deficits are inherently unfair. For decades, he has argued that if the U.S. buys more from a country than it sells to them, it must mean the U.S. is being cheated. This thinking goes back at least to the 1980s, when in The Art of the Deal Trump blamed Japan for "screwing the United States." Later, in The America We Deserve, he pointed to the trade deficit as proof that America was being "ripped off by virtually every country we do business with."

Now, I’m no economist, but Trump is utterly clueless. He has never understood that voluntary trade benefits both sides. Instead, he sees trade as a zero-sum game—a contest where if one country wins, the other must lose. This economic illiteracy led to his first-term tariffs on China and the EU, and it fuels his new "reciprocal tariffs," which aim to mirror trade deficits dollar for dollar with import taxes—even against allies like Israel (but not Russia).

Even though Trump originally opposed tariffs in his early books, by 2011's Time to Get Tough, he was fully on board. He promised to punish China for its currency manipulation and trade surplus with the U.S., calling for tariffs and referencing supply-side economist Peter Navarro to claim the deficit cost America a million jobs a year. Navarro would go on to be one of Trump’s top trade advisors, championing "economic nationalism."

Despite renegotiating trade deals like NAFTA (now USMCA) and pulling out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Trump's first term ended with a higher trade deficit—$626 billion in 2020 compared to $503 billion in 2016. Meanwhile, tariffs raised prices for American consumers and disrupted supply chains. But Trump remained unfazed. In his words, “Tariffs are the greatest thing ever invented.”

Now, Trump is going even further. New proposed tariffs would raise average U.S. duties to levels not seen since the Great Depression—even higher than Smoot-Hawley. University of Michigan economist Justin Wolfers notes that Trump’s latest tariffs could raise rates to fifteen times their 2016 levels.

Whether this is a negotiating tactic or a long-term strategy remains unclear. Trump’s rhetoric is contradictory: sometimes tariffs are a means to force better deals, other times they're an end in themselves. But with his obsession over trade deficits and his belief that the world is laughing at America, there’s a real risk he’ll escalate regardless of the consequences.

The deeper lesson of Smoot-Hawley is that economic nationalism and protectionism often lead to global retaliation, economic contraction, and long-term harm. As Trump revives these ideas under the guise of “reciprocal” fairness, history may be poised to repeat itself—unless cooler heads prevail, or Trump’s craving for a “deal” overrides his protectionist instincts.

We’ll see how the leaders of other nations deal with this man-baby, They probably know their history and do not want a repeat of the 1930s. They will of course know that the simplest way to Trump’s heart is to stroke his ego. Generally, his narcissistic needs can be employed to lead Trump to a desired outcome. We can only hope that life-long vanity wins out over new-found ideology.

Addendum: It appears that Republicans are getting a bit queasy about Trump’s tariffs, and other pundits are writing about it.