Pine Leaf

This is a reprise of a story with some new information added. It was originally published 20 November 2021, to The Jon S. Randal Peace Page for National Native American Heritage Month, created to share awareness and promote understanding. It was the third in a series of five articles, all histories of Two Spirit Native Americans. The first was the story of Osh Tish, which was reprised here just a few days ago. A few of the comments on that story indicated that the status of Two Spirit Natives had not been known, so I have decided to run this story again.

The history of the people present in the “New World” before the arrival of European colonizers is a muddled one. The one thing of which we are certain is that the explorers found nothing new―only things and people new to them. The civilizations found had occupied these lands for millennia. We must give the anthropologists a great deal of credit―ferreting out what is fact and what is legend is a time-consuming and often unrewarding task.

According to linguist and anthropologist Lyle Campbell, "no native writing system was known among North American Indians at the time of first European contact, unlike the Maya, Aztecs, Mixtecs, and Zapotecs of Mesoamerica who had native writing systems."

While some of the southern tribes of North America had developed some rudimentary sets of symbols. Among those were possibly the Cherokee and those of the Caddoan bloodline. The northern peoples, including the people of the Algonquin bloodline, had no written languages.

We have our clues. There are pictographs found in caves, and on the sheltered walls of bluffs. The people we wish to learn about had oral histories passed down by tribal storytellers from generation to generation. These sources provide considerable information, yet until the 19th century, there was very little set to paper.

The writings that we have, those penned in more recent history, can themselves be less than helpful. Much of it has proved biased or otherwise inaccurate. Since we cannot fully trust it, we revert to that which we can place our hands on. Mainly, we rely on the storytellers and the artifacts, and then we select the parts of those written histories that concur in order to construct accurate timelines. The most reliable data comes from verifying certain details by comparing it to unrelated sources.

The telling of these stories for those of us not born into that world can be challenging. I do not claim to be an authority—only a student of those who are.

Looking back, the previous two stories in this series focused on some of the larger plains tribes―the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Apsáalooke (Crow), and Shoshone. Although each tribe was distinct from the others, oral histories, anthropological evidence, and genetics link many of them to a single, large nation―the Algonquin of the Great Northeast and Canada. The Sioux may be an exception to this link.

When European explorers arrived on the Atlantic coast, the natives they met first were of the Algonquin or related tribes. At Jamestown they encountered the Powhatan. The Pequots, Narragansetts, and the Wampanoag greeted the Pilgrims and the Puritans. William Penn’s first encounter was with the Leni Lenape.

Over the centuries, before European arrival, the Algonquin nation had given birth to many descendent tribes, and many of those had splintered into other tribes. The mother tribe can still be found in large numbers living in their traditional lands of the Great Lakes and Northeastern Canada regions, making them one of North America’s longest-lived nations. They live there along with several of their descendant tribes―the Odawa, Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Oji-Cree, and others. Together these tribes form the larger Anicinàpe nation―the first known people to inhabit the Quebec region.

By tracing the native languages of the plains tribes, we find many rooted in the Algonquin language family. Anthropologists have found evidence that by the late seventeenth century, many of these Algonquin offshoots had become rivals, as was the case with the A'aninin and Arapaho―two tribes once united. The Arapaho were, in fact, a secondary offshoot.

The A'aninin, meaning 'White Clay People,' were a direct offshoot of the Algonquin, named for their ancestral belief that all people were created from the white clay along local riverbanks. When French explorer Champlain arrived in their lands, they became known as the Gros Ventre (pronounced “Grow Vaunt”).

By the time the U.S. was at war with the Cheyenne and the Sioux, the Gros Ventre were one of the smallest plains tribes. Historical evidence suggests they had once been a great nation, with villages stretching from Hudson Bay to the Rocky Mountain foothills.

The Cheyenne, also an Algonquin splinter, became allies with the Arapaho, who had acrimoniously split from the A'aninin many years earlier. The two allies migrated first into Montana, then later further south into Wyoming and Colorado. The Shoshone moved south and west, making the northern plains their hunting grounds, while at the same time crowding them into the foothills of the Rockies.

Years earlier the Spaniards had introduced horses into Mexico. Inevitably, some escaped and wandered northward. At some point they were found by the Shoshone. This chance encounter gave birth both to a new food source, and to the premiere horse cavalry of the plains―the Comanche.

Back up in the north country, the A'aninin had split for a second time―this time harmoniously – becoming the larger, northern tribal group and the southern tribal group. The southern group were often called Hidatsa. Both were known as Gros Ventre.

Tribal names translated into other languages can be a funny thing. Gros Ventre originated from a misinterpretation of sign language. The sign to indicate they were the A'aninin was an open hand rubbing the abdomen. When an A'aninin hunting party made initial contact with the French, Champlain’s scouts misunderstood the sign. The scouts believed the natives were indicating that they were paunchy, or big bellied. In French, “paunch” translates to Gros Ventre. In English they became known as the “Big Belly.”

Over the years the Gros Ventre suffered many misidentifications – some honest mistakes and others meant as insults. An early enemy, the Piegan Blackfoot, called them by a word that translates to "snake." The Arapaho looked upon the Gros Ventre as inferior, calling them "beggars."

The Gros Ventre acquired horses in the eighteenth century around the time of their first known contact with European settlers. It was also the time when vulnerable natives were being exposed to smallpox. Weakened by losses to the disease, the tribe fell victim to attacks by neighboring enemy tribes―Cree, Blackfoot, Assiniboine, Crow, and others.

Following one of the more costly attacks on a Gros Ventre village by a Blackfoot raiding party, recognizing that they had been attacked with weapons acquired from white settlers, the tribe’s warriors attacked the origin of those weapons. They burned two Hudson Bay Company trading posts. It did little good. The Gros Ventre remained a weakened nation that fell prey to many enemies, now including the white traders.

In the very early nineteenth century, having never fully recovered from the smallpox epidemic and still under continual attacks from Cree and Assiniboine, the Gros Ventre migrated southward to Missouri River country. Their location on the northern plains remained perilous – wedged into an area surrounded by enemies. The Blackfoot were to their west, the Assiniboine were to their east, and now they had Crow to their south.

Smallpox hit them twice more since that first killing epidemic. It came in 1801, and then again in 1829. The tribe was reduced well below fighting strength and might have perished were it not for bitter irony. The Blackfoot and Assiniboine both fell victim to the same disease.

This left only the Crow, who had somehow managed to avoid contact with the disease. Crow war parties continued raiding Gros Ventre camps. The two tribes remained bitter enemies for years, with wars between them lasting well into the reservation period.

Around 1805 or 1806, during one of their most vulnerable times, a girl was born into the Gros Ventre. Her name was Barcheeampe, meaning Pine Leaf. She would later become Biawacheeitche―the Woman Chief.

This is her story.

At around 10 years of age Barcheeampe’s village was attacked by Crow raiders. Many of their young men were killed, with women and children kidnapped. Barcheeampe was one of those. She was taken into the lodge of a Crow warrior, a chief, and raised as Crow. She grew to become a Crow woman―later becoming a Crow warrior. With her family lost, her ties to the Gros Ventre faded.

From a young age, she was remarkable. According to the journal of fur trader Edwin Thompson Denig, who knew her for several years, she could 'rival any of the young men in all their amusements and occupations.' She was 'fearless in everything' and adept at hunting and warfare. Even when very young, she showed a preference for traditional male interests. Denig initially took time to understand her as Two-Spirit, and even longer to grasp its significance.

Denig writes that her adopted father encouraged the male pursuits. He had lost his sons to past battles and was glad that he might have another warrior in his lodge. She proved herself to be very talented with a horse, excellent with a gun, and skilled in hunting. As a hunter, she showed talent in her ability to quickly field-dress buffalo.

The Crow acknowledged her as a Two-Spirit woman, yet unlike other Two-Spirits, she wore clothing more typical of a woman. Outside the tribe, others found this confusing. They were not confused by her abilities.

According to the Jennifer L. Jenkins book, "Woman Chief," when the Blackfoot raided the fort where Crow and white families were sheltering, she is said to have “fought off multiple attackers and was instrumental in turning back the raid.” Her actions that day elevated her status, and when her father died, “it was understood that she would become the leader of his lodge.”

Jenkins writes that over the next few years she would lead “large war parties, and was recognized as the third highest leader in a band of 160 lodges.” Although she wore the dress of a woman she kept up “all the style of a man and chief … She has her guns, bows, lances, war horses, and even two or three young women as wives ... the devices on her robe represent some of her brave acts.”

Along with her band of warriors, she “raided Blackfoot settlements,” says Jenkins, “taking off many horses and scalps. For her deeds she was accepted to represent her lodge as bacheeítche (chief) in the Council of Chiefs. It was at this time that she earned the title of Bíawacheeitchish, or Woman Chief.”

“Her prestige and wealth quickly increased, and she took four wives,” said Jenkins. Following the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie, she was entrusted to sit in negotiations with the other tribes of Upper Missouri, seeking to bring peace between the Crow and the Gros Ventre.

Legends of Pine Leaf, the Woman Chief, are still told among the Crow. As one such legend tells it, in her first battle she killed two enemy warriors and captured a herd of horses from a nearby field. The tale is likely exaggerated, yet the core of it is based in fact. The Jenkins book corroborates that much.

Another legend says that she swore not to take a husband until she had killed 100 foes. Although there is nothing other than oral history to validate this claim, it shows that she was obviously a very important part of Crow history. If the tales of her heroism can be believed, she may have met her goal, although she never took a husband.

Travelers who met her wrote accounts of their encounters. The fur trader Edwin Denig and a traveler named Rudolph Kurz both found her an enigma worthy of recording in their journals. Denig wrote that she was “an exotic figure among the patriarchal Crow.” Both Denig and Kurz likened her to the Amazon women of European myth. Their accounts are limited by their lack of understanding of Two-Spirit identities, yet still offer useful insights into her life.

It is from fur trader James Beckworth’s memoir that we learn some of the more intimate side of the Woman Chief known as Pine Leaf. Beckworth was a formerly enslaved Black man—a fur trader and mountain man who had the experience, and possibly misfortune, of falling in love with Bíawacheeitchish. The concept of Two-Spirit was apparently foreign to him. He wanted her for his wife. She refused his marriage proposals many times before finally agreeing to marry, but only “when the pine leaves turn yellow.”

Later it occurred to Beckworth that pine leaves don’t turn yellow. I suspect that at that point all he could do is smile.

It is bitter irony that in 1854, when Bíawacheeitchish, the Woman Chief of the Crow, went on a peace mission to a Gros Ventre camp, that she was ambushed and killed by members of the tribe of her birth. Believing in the possibility of peace, she had come unarmed.

Pine Leaf’s life is a story of strength—a journey that took her from a captive child to respected chief, and ultimately, a seeker of peace. Born into the Gros Ventre, raised by the Crow, and later betrayed by her people of origin, she defied the expectations imposed upon her, carving out a path as a warrior, leader, and bridge between warring nations. As a Two-Spirit, she embodied both masculine and feminine qualities, earning respect not only for her strength and skills in battle but for her wisdom and willingness to pursue peace. Her life is a reminder of the strength found in embracing diversity within ourselves and our communities. She was a warrior who came to embrace peace.

Imagine what this world might be like if modern cultures could open their hearts to that kind of wisdom.

Author’s Notes:

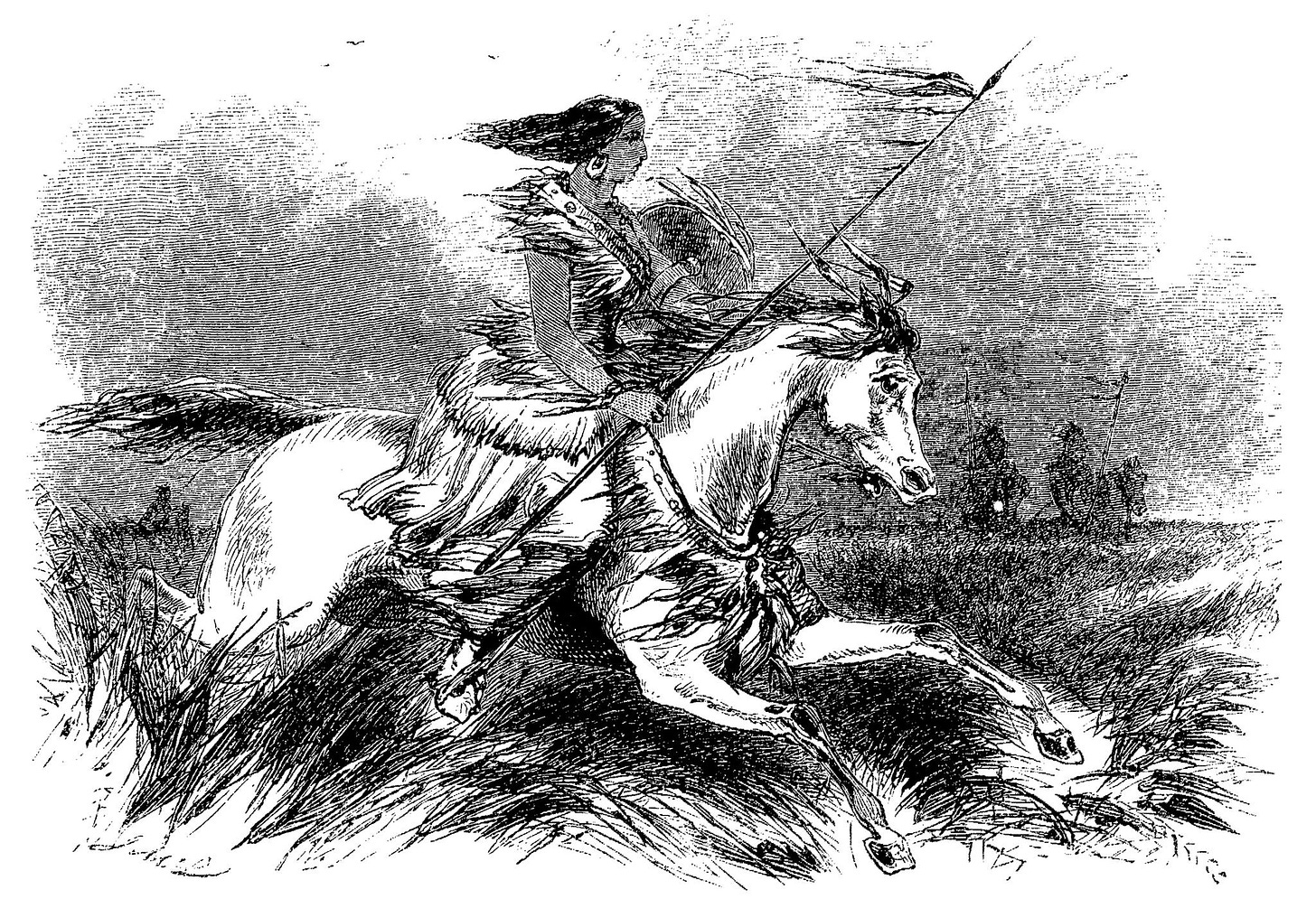

The somewhat blurry illustration was drawn by James Beckworth, and published in his memoir.

Two-Spirit is both an ancient and a modern term. The early Ojibwe are believed to be the origin of the term, and it may have been used by others. If true, that would place the term is several centuries old.

Researcher Beatrice Medicine, writing in the paper, “Directions in Gender Research in American Indian Societies: Two-Spirits and Other Categories,” says that the term “was adopted at a 1990 Indigenous lesbian and gay international gathering to encourage the replacement of an anthropological term used earlier.”

The term replaced was “Bardache,” which could have meanings ranging from “gay” to “male prostitute” to “slave.” Two-Spirit is a term “defining the spiritual role recognized and confirmed by the modern Two-Spirit’s indigenous community. Not all Native cultures conceptualize gender this way, and most tribes use names in their own languages.”

Cultural anthropologists generally agree that Native-Americans having characteristics of both female and male were considered, at least by most nations, to be gifted―seen as doubly blessed with the spirits of both man and woman. Two-Spirit people often became religious leaders or teachers. In the old days, Two-Spirits were revered. Today, many Native Americans have adopted the white disgust for LGBTQ+ people and they are denied human rights, often rejected, abused, or mistreated.

Information for this story comes from the following sources:

University of Colorado anthropologist Andrew Cowell’s recently published paper titled “Gros Ventre; ethnogeography and place names. A diachronic perspective.”

The Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. 1: Part IV.; Ethnology of the Gros Ventre.

The Website “Algonquins of Ontario.”

“Native New Yorkers: The Legacy of the Algonquin People of New York” by Evan T. Pritchard