Yesterday we visited the tangled world of social safety net programs in America―specifically with regard to food assistance. Today I want to cover the two-decade period spanning the administrations of two Democratic presidents. The first faced a nation in dire condition due to a natural disaster and exacerbated by man-made failure. The other looked into the eyes of hungry children and knew he must do something. The latter at a time when Americans were shaken by the discovery that even in this country, there were poor people going hungry. This piece is mostly a reminder of our shared history, with a bit of opinion added for spice.

As mentioned yesterday, farmers have long been the backbone of America. Many farm families, spanning multiple generations, have worked tirelessly to feed the nation while supporting their communities. Since the late 1960s, however, their political loyalties began shifting to the Republican Party. This article ends around the time of that change and explores why, between the 1940s and the mid-1960s, farmers’ political opinions were more favorable toward Democrats.

Like most political shifts, the migration of American farmers from supporting Democrats to aligning with the Republican Party was a gradual process shaped by a complex mix of factors, including economic transformations, policy changes, cultural shifts, a rise in Christian conservatism during the Red Scare, and, as with many aspects of American politics, an undercurrent of home-grown racism.

On the political front, the Republican Party attracted farmers with promises of lower taxes, fewer regulations, and a commitment to rural values. However, the notion of “rural values” subtly incorporated racial biases, the so-called “over-regulation” was often found to be beneficial for agricultural or environmental stability, and the promise of lower taxes ultimately proved to be more myth than reality.

Between President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and John F. Kennedy's first Executive Order, U.S. government food assistance programs both emerged and evolved. In the 1940s, these initiatives primarily aimed to alleviate hunger among Americans left destitute by the Great Depression and the collapse of the nation’s banks. They also provided crucial support to farmers struggling after the Dust Bowl years, which had devastated entire farmsteads and left vast areas of land fallow. Recognizing the need to stabilize the agricultural economy during this period of economic hardship, the Roosevelt administration implemented policies to support both consumers and producers.

This article explores the development of food assistance programs by examining the perspectives of politicians, economists, farmers, and beneficiaries. Along the way, I will also provide political context to illustrate how these programs influenced the political realignment of American farmers—while acknowledging that most farmers may not agree with my perspective.

To understand this shift, we must first examine the origins of American food assistance programs, how they benefited the nation’s poorest, and how farmers historically prospered under Democratic administrations while facing challenges under Republican rule. The lingering question, however, is why farmers continued to vote against their own economic interests.

The Dust Bowl years devastated much of the nation’s farmland and forced many farmers out of business just as the Great Depression plunged millions of Americans into poverty and hunger. Paradoxically, while many faced severe food shortages, farmers in areas unaffected by the Dust Bowl struggled with surplus produce and plummeting prices.

To address the surplus issue, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration initially paid farmers to destroy crops and slaughter livestock to create artificial scarcity and raise prices. However, as historian Christopher Klein noted, “The destruction of food at a time when so many stomachs rumbled sparked public outrage.” In response, the Federal Surplus Commodities Corporation (FSCC), a New Deal agency established in 1933, began purchasing excess food and distributing it to those in need. While this eased hunger, it also drew criticism from grocers and food wholesalers who accused the government of unfair competition. The administration was catching it from all sides.

To balance these competing interests, the Roosevelt administration implemented the Agricultural Adjustment Act in 1933, which aimed to stabilize agricultural prices by reducing surpluses. The government purchased excess commodities from farmers and distributed them to those in need, laying the groundwork for future food assistance programs. This strategy not only supported struggling farmers but also helped to address the growing issue of hunger among the urban poor.

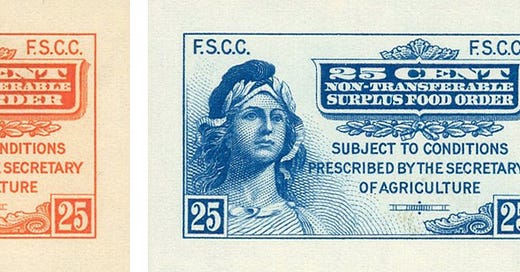

The first Food Stamp Program (FSP), conceived by Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace, was launched as a pilot in 1939 and designed as a pay-as-you-go system. Participants purchased orange stamps at face value, which could be spent like cash on any food items.

For every dollar spent on orange stamps, participants received an additional 50 cents' worth of blue stamps for free. Unlike the orange stamps, blue stamps were designated for purchasing surplus foods the government aimed to distribute, such as dairy products, eggs, and fresh produce. On the first day of issue, Rochester, New York resident Ralston Thayer used $4 from his unemployment check to purchase $4 of orange stamps, receiving $2 of blue stamps at no cost. “I never received surplus foods before, but the procedure seems simple enough and I certainly intend to take advantage of it,” Thayer told reporters.

This system ensured that recipients contributed to their food purchases while benefiting from the added value of the blue stamps, effectively connecting consumer needs with agricultural support. It allowed low-income families to stretch their food budgets while helping farmers reduce agricultural surpluses. Opponents, however, argued that such programs could foster dependency among recipients and expand the federal government's role in welfare.

However, the pay-as-you-go structure of the FSP countered some of these criticisms by requiring participants to invest their own money, promoting personal responsibility and reducing concerns about dependency. This approach challenged the notion that food assistance programs were merely charitable handouts, as recipients played an active role in their own food purchases.

By 1938, the federal government was purchasing, transporting, storing, and distributing massive amounts of food to state and local relief agencies. Although these efforts were significant, they were not without challenges. Managing surplus commodities and ensuring timely delivery to those in need proved complex, leading to frequent delays and logistical inefficiencies.

Building upon earlier relief efforts, the first Food Stamp Program was piloted in 1939 under the leadership of Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace and Administrator Milo Perkins. The program aimed to assist low-income individuals while supporting the agricultural economy. Participants purchased orange stamps to cover their normal food expenses and received blue stamps worth 50% of their purchase for surplus foods.

Milo Perkins summarized the program's dual benefit, stating, "We got a picture of a gorge, with farm surpluses on one cliff and under-nourished city folks with outstretched hands on the other. We set out to find a practical way to build a bridge across that chasm." This metaphor highlighted the program's goal of connecting surplus agricultural products with the nutritional needs of the urban poor. However, the program faced criticism—not only from Republicans and Southern Democrats but also from some Civil Rights leaders—who interpreted the initiative through their own political lenses.

Republicans opposed the program, claiming it encouraged dependency among the “lazy” poor. Southern Democrats objected on states’ rights grounds, fearing that the program would benefit Black communities in the South, challenging the existing racial and economic hierarchies. Meanwhile, some Civil Rights leaders criticized the program for failing to address the severe economic disparities faced by Black Americans, arguing that it did not adequately support marginalized communities or ensure equitable access to resources.

Roosevelt, along with Wallace and Perkins, demonstrated the program’s effectiveness despite opposition from Republicans, Southern Democrats, and Civil Rights leaders. Their efforts highlighted the program's dual success in alleviating hunger and stabilizing the agricultural economy. More on this political resistance will be explored later in this story.

The initial FSP concluded in 1943, having served approximately 20 million people across nearly half of the counties in the United States. As World War II bolstered the economy, increased employment reduced the demand for food assistance while agricultural surpluses declined. Consequently, the program was deemed no longer necessary and was phased out.

Following World War II, the U.S. experienced economic growth, but poverty and hunger persisted, particularly in communities with large Black populations. During the 1950s, debates continued over the government’s role in providing food assistance, but no consensus was reached, and little action was taken. Meanwhile, racial discrimination remained pervasive, and Black unemployment rates remained disproportionately high.

While Republicans and Southern Democrats showed little concern, a Democratic Senator from Massachusetts, John F. Kennedy, was actively advocating for change. In 1959, during a “Bean Feed” event in Minneapolis, Kennedy criticized criticized the Eisenhower administration's handling of food surpluses, stating, “Nixon promises to use the food surpluses of our country to take care of the needy abroad and the needy at home. Food for peace was devised by Hubert Humphrey. It was never supported by the administration.”

Kennedy continued to advocate for reinstituting the FSP despite criticism. At the time, some economists argued that distributing surplus food could distort markets and lower prices, harming farmers. Others believed that government intervention was necessary to address market failures and ensure food security for vulnerable populations. Meanwhile, Republicans and “Dixiecrats” voiced strong opposition, arguing against expanding federal welfare programs.

Kennedy’s advocacy helped renew the focus on food assistance in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Writing in his 1983 book, The Other America: Poverty in the United States, Michael Harrington noted, “The popular discovery of poverty in the United States only occurred in the 1960s, but with that discovery came controversy over whether the Federal Government was doing enough to alleviate it.”

Shortly afterward, reports of widespread hunger in the U.S. spurred public concern and political action. In 1960, Kennedy visited Mount Hope, West Virginia, where he witnessed firsthand the severe poverty faced by local families. He remarked, “I want to talk with you today about the most fundamental subject in life – food. Most of the nation takes food for granted.”

Continuing his speech, Kennedy observed, “[m]ost of the nation takes food for granted. When I spoke recently about the millions of Americans who go to bed hungry each night, my speech was criticized by the Wall Street Journal. Impossible, they said. Not in America. Not with all our prosperity and all our food surpluses and all our welfare programs. But the Wall Street Journal ought to come to West Virginia, to this county and to other counties like it. Because people are hungry here - prosperity has passed them by - food surpluses are rotting in warehouses - and welfare programs are not enough.”

In response to growing public concern, the Kennedy Administration actively sought new approaches to provide food assistance. The concept of food stamps was revisited, leading to pilot programs that eventually culminated in the Food Stamp Act of 1964. This legislation aimed to strengthen the agricultural economy while ensuring better nutrition for low-income households.

Farmers had mixed reactions to food assistance programs. Some appreciated the government’s purchase of surplus produce, which provided a stable market and steady income. However, others were concerned about becoming too reliant on government purchases, fearing that market distortions could lead to lower prices and reduced profitability.

Despite the program’s intent to encourage personal responsibility and support the agricultural economy, it faced opposition from some Republican lawmakers. Critics argued that the FSP was essentially just a welfare initiative, and in those days, Republicans had made “welfare” a dirty word. Iowa Republican Congressman Charles B. Hoeven notably referred to it as a “welfare program under Agriculture control.”

Although the American public was only beginning to understand the extent of poverty and hunger in the U.S., politicians were well aware—and many Republicans were content to ignore the issue. Years after Kennedy’s West Virginia speech, in a New York Times interview, U.S. Attorney General under President Ronald Reagan, while railing against welfare, stated, “We do not know how many people there may be who are hungry. We also do not know why there is hunger in this country, to whatever extent it exists, at a time when the Federal Government, state and local governments and private organizations are spending more on food assistance than ever before in history."

It was in the early 1960s when Kennedy reinstituted the Food Stamp Program, and beneficiaries frequently expressed gratitude for the support during difficult times. One recipient noted, “The food stamps have been a blessing. Without them, I don’t know how we would have managed to feed our children.” Such testimonials underscored the importance of these programs in alleviating hunger and providing a safety net for vulnerable populations.

One of the most significant impacts of food assistance is its role in breaking the cycle of generational poverty. Food insecurity, defined as the lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life, poses severe risks for children. Those experiencing food insecurity are at increased risk of developing physical and mental health problems, including obesity, anxiety, depression, and behavioral issues. This is partly because they may rely on high-calorie, low-nutrient foods that are cheaper and more accessible.

Malnourishment has a profound effect on children’s academic performance. Without consistent access to nutritious meals, children struggle with concentration and memory, and many of them experience learning difficulties, hindering their ability to succeed in school. Over time, these challenges can limit educational and economic opportunities, perpetuating a cycle of poverty. Without intervention, many of these children are at risk of lifelong marginalization.

Between the Roosevelt and Kennedy administrations, U.S. government food assistance programs evolved in response to economic challenges, political debates, and social needs. These initiatives not only provided essential support to those facing hunger but also played a crucial role in stabilizing the agricultural economy. The legacy of these early programs laid the foundation for modern food assistance efforts, demonstrating a continued commitment to addressing food insecurity in America.

This analysis has covered the two presidential administrations that established food assistance programs. In contrast, Republican administrations have generally sought to reduce or eliminate safety net programs that have helped thousands of impoverished Americans avoid food insecurity, or like Eisenhower, simply do nothing.

Republicans claim that they too have supported programs that benefit the weakest among us. This is, to a large degree, a fiction. Republican ideals, while they may have been altruistic many years in the past, are nothing of the sort today. We will explore that in Part three, which may or may not be published tomorrow.

While Republicans have occasionally supported programs aimed at helping vulnerable populations, such support has often been limited or conditional. Although Republican ideals may have been rooted in altruism in the past, contemporary policies have frequently prioritized economic austerity over social welfare.

This shift will be explored further in Part Three.