In 1901, budding real estate developer Joseph J. Asch built a ten-story building in New York City. He had John Woolley design it to his specifications. The location was in a nice area at the corner of Greene Street and Washington Square East, in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan. It was a stupendous building ― constructed not of wood, but of brick and iron, with a neo-Renaissance design.

Asch named it after himself.

The Asch building is the only reason we know the name of Joseph J. Asch. History only records him for this one, rather hum drum achievement ― then obscurity. The building shed his name a long time ago and is now the Brown Building ― part of the campus of New York University. Just another old building in Manhattan.

Except for the three bronze plaques on the southeast corner of the building, memorializing the 125 girls and women, and the 17 men who lost their lives in that building on 25 March 1911.

Asch had advertised the building’s "fireproof" rooms. That was an attractive feature, especially for garment manufacturers. So attractive that one such manufacturer quickly took out the top three floors of the building.

Then ― just as the promise of the Titanic failed a year and a month later, so did the promise of the Asch building on that fateful day in March 1911.

I suspect that by now, many of those reading this have figured out that the fire I mention was the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire. We mention and dissect it here reluctantly ― regretfully ― only as a means to an end.

If we are going to dissect it, we need to know what happened, so we ferret through the documents and the reports found in the historical record to see what the investigators determined.

The first item they noted was obviously, an unsafe work environment. Specifically, the rooms were overcrowded. Ventilation was inadequate, resulting in heavy dust concentration in the air. Flammable materials were in abundance.

Because the building was considered fireproof, only a single fire escape was available to serve the entire building. Sprinkler systems were not installed. By the standards of the day, no law required fire sprinklers, fire escapes, or outward opening doors. All of this was up to the discretionary power of the building owners.

The weightbearing capacity of that single fire escape was insufficient to allow the number of people on that day to make it safely to the ground. It collapsed while in use. Even before it fell, others had died or were injured jumping from the lower ladder, which did not extend downwards far enough.

The investigators also noted unsafe working conditions. Workers were squeezed against each other, causing the rooms to be crowded. The rooms, aisle, and doorways were at points obstructed by materials or equipment.

Flammable objects, including the material from which the workers sewed the garments, cuttings dropped to the floor with no effort to remove them, and clothing patterns made of tissue hanging from lines above workers' heads.

The rooms were overcrowded with workers (there was no limit at the time as to how many people were permitted to occupy one floor) and rows of tightly spaced sewing machines, cutting tables stacked with bolts of cloth, and the carts to move them reduced the width of aisles, slowing escaping workers.

From the reports, we can easily see that it was an accident waiting to happen. Worse. It was a trap.

Survivors reported fabric cuttings littering the floors, and there was obviously material on the worktables, that, when combined with the tissue patterns, provided fuel for the fire.

All that required was a spark.

One the few survivors reported a blue glow coming from a bin under a table where 120 layers of fabric had just been stacked prior to cutting. She did not recognize it for what it was.

The origin of the fire remains unknown, but the woman said she saw it rise from the bin where she had earlier seen the glow. Flames, at first contained to a small area, soon began lapping into the air up until the tissue paper ignited. As it burned, glowing fragments floated into the air and drifted around the room. The embers landed on tables piled with fabric all around the room, and on the floor where the cuttings caught fire.

From that point it was panic and conflagration.

Escape routes to the interior stairs were blocked or restricted by bales of material and the carts used to move them. Frantic workers piled up at the entrance of the stairway, which had no landing and no lights, leaving those attempting to escape in total darkness. This slowed their progress and created a logjam.

The foreman was in the habit of locking doors that would have led to escape, because the owners wanted the women to take no breaks and thereby increase production. In the panic, workers were crushed to death as they stacked up against the locked doors attempting to flee. Others slowly suffocated and burned.

The factory owners and their families escaped using an elevator which could have held a dozen more people, then told the operator to take it back up. It malfunctioned on its second trip, possibly because of the heat. The operator hopped off and fled.

The fire, which had started on the eighth floor, quickly reached the ninth by racing up the stairwell, and with the fire escape crumbled to the ground below, the elevator stuck in the shaft somewhere below, and all other exits either locked or engulfed in flame, the workers began jumping. Only a very few of the survivors had been on those top two floors.

Those were the findings from the reports I have read. There were other reports, but I could take only so much gore in a single dive. This paints a sufficient picture.

The reports found fault with the foreman’s actions and the factory owners for allowing it, and for not filling the elevator on their descent with more who might have survived.

Most of the workers who occupied the Asch Building, and not just at Triangle (were female immigrants. All ten floors were full of sewing factories. The men that were there were either supervisors or heavy lifters ― strong men who could move the huge bales of fabric around ― mostly Black men.

Immigrants came to the United States from foreign lands to escape famine, war, poverty, in search of a better life, or just out of curiosity. This is nothing new. The U.S. is a nation built by immigration. These are without question the reasons immigrants have come to this land since Europeans first stumbled upon it.

And rich Americans, industrialists by the time of this fire, have preyed upon immigrants from day one. Immigrants would often agree or could be made to work in substandard conditions and for near starvation wages, with little complaint. It was better than where they came from.

American industrialists learned this from their European homelands, where the same had been practiced for who knows how long, but at least since the days of feudalism.

It is pure and simple greed that drives them to prey upon the weak, and it was greed that led to the Triangle Shirtwaist tragedy.

Yes, I know that not every rich dude is a predator, but I defy you to prove me wrong for saying that the overwhelming number of them were and still are.

Regardless, when the fire was finally out and the smoke had cleared, because of greed, one hundred and forty six lives were snuffed out in 18 minutes or less. Roughly a third of them jumped to their deaths rather than be burned alive.

There were survivors. Not many, but some who could reveal the details. Enough to confirm the conditions and the cruelty.

Some determined, with little evidence, that it was just a dropped match, but there was also sinister innuendo about the cause of the fire. Innuendo that remains today.

According to writer Jeanette Lamb, “The factory had not been doing well financially. It was not the first time Max Blanck and Issac Harris, the factory owners, saw their business go up in flames. Their four previous businesses were also destroyed by fire. Despite that, and that at the time in New York City, the fashion district was plagued by fires, most of which had impeccable timing.”

Like when business was falling off?

Blanck and Harris had also just taken out a large insurance police, which according to Lamb, specifically paid out “if they lost workers to death or injury.”

Arson charges were never filed against the two, but they were both charged with manslaughter.

For me, one of the most disturbing parts of this story has always been what happened next. One hundred and forty six broken or charred bodies were removed and transported to the morgue, where many of them remained for many weeks. Some could not be identified, and some had no one known who could identify them, but the delay was mostly because New York City could not quickly find that many cheap coffins.

Heartbreaking does not begin to describe the Triangle Shirt Waist factory fire. Americans felt the suffering to their very core, and some stepped up to do something about it. These poor souls could not be saved, but New Yorkers were going to make sure others didn’t face the same choices at the immigrants at Triangle.

New Yorkers and people everywhere were moved by this senseless loss of life. When organizers staged a funeral march for the victims, more than 350,000 people marched with them. Protests began to erupt around the city.

So, why am I talking about that terrible fire in September when it happened in March? Easy answer ― today is the first day of the Labor Day three-day weekend ― the unofficial end of summer. I hope you enjoy the time off work, or your time with family.

As to why this day is recognized, let’s circle back the Triangle again.

After the funeral march in New York, activists immediately hit the streets and did what activists have always done. First, they organized a movement to keep the memory of the Triangle workers alive, then they began lobbying their local and state leaders, according to Dr. Howard Markel, “to do something in the name of building and worker safety and health. “

“Three months later, John Alden Dix, then the governor of New York, signed a law empowering the Factory Investigating Committee, which resulted in eight more laws covering fire safety, factory inspection, and sanitation and employment rules for women and children,” Markle continues. “The following year, 1912, activists and legislators in New York State enacted another 25 laws that transformed its labor protections into among the most progressive in the nation.”

These reforms — all intended to protect the health and safety of the American worker — were used as models in the creation of federal law during the New Deal. Franklin Roosevelt was also moved by the senseless loss of life.

Eventually the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU) formed and continued to fight for better working conditions for sweatshop workers in New York, the United States, and beyond. The ILGWU became one of the largest labor unions in the United States, at one time bragging of a membership of almost a half million. The union that became a key player in the labor history of the 1920s and 1930s merged with the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union in the 1990s to form the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE).

Over three decades later, in 1970, Congress passed the Occupational Safety and Health Act, which created, according to Markle, an agency “whose primary mission is to ensure that employees carry out their tasks under safe working conditions.”

OSHA famously created a thick manual of regulations, honed into specifics to fit every industry, and because of that, OSHA became a prime target for anti-regulation politicians, who are of course responding to pressure from business-owning donors, but so far OSHA has survived and remains a critically important agency in the lives of working Americans.

The rules didn’t get plucked out of thin air. There are reasons for them. As an industrial safety man I know once said, “Every regulation in that book has someone’s blood on it.”

And that, my friends, is the reason unions support OSHA.

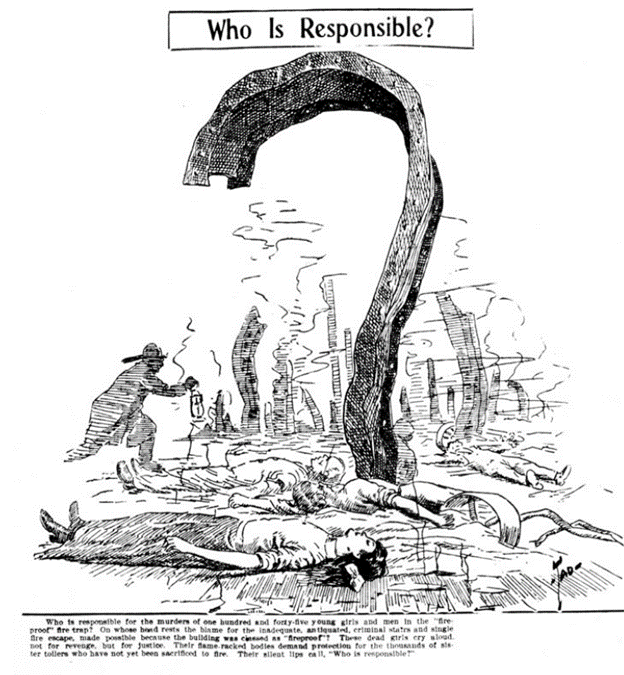

The caption reads:

“Who is responsible? Who is responsible for the murders of one hundred and forty-five young girls and men in the ‘fire proof’ fire trap? On whose head rests the blame for the inadequate, antiquated, criminal stairs and single fire escape, made possible because the building was classed as ‘fireproof’? These dead girls cry aloud, not for revenge, but for justice. Their flame-racked bodies demand protection for the thousands of sister toilers who have not yet been sacrificed to fire. Their silent lips call, ‘Who is responsible?’”